I recently watched this short video by Ward Cunningham where he reflects on the history, motivation for, and common misunderstandings of the term Technical debt.

This post is just some of my reflections on Technical debt, based on ideas and thoughts from Ward Cunningham, Martin Fowler and Uncle Bob.

What is Technical Debt?

Ward Cunningham coined the “Techincal Debt” metaphor – he used the metaphor to explain the idea of shipping something with a limited understanding of the problem, in the hope of gaining a better understanding as more people interact with the shipped code.

The difference between the understanding of the problem and how the code models it is going to slow down the developers. This “slowing down” is equivalent to paying interest, until we take out the time to refactor the code to accurately reflect the current understanding of the problem.

Why take on Technical Debt?

When Cunningham says debt, he means shipping code with a partial, unclear or even incorrect understanding of the problem and how it should be modeled. You are willing to get the code out of the door, to improve this understanding.

With borrowed money, sometimes you can do something sooner than you would otherwise. Similarly, rushing software out the door can help us get some experience with it, which would help gain a better understanding and improve the software.

A mess is not a debt, or is it?

Cunningham says that people confuse messily written code with technical debt. He is of the opinion that messy code isn’t technical debt. He’s never in favor of shipping bad or messy code. He emphasizes that code that’s shipped should always be clear enough to refactor easily, when required, even if it doesn’t model our current understanding of the problem very accurately.

Uncle Bob also has a post, on similar lines, where he says, a mess is not a technical debt.

Martin Fowler, on the other hand, argues that the debt metaphor is a useful metaphor to think about and to communicate problems in code — especially to non-technical people — irrespective of the reason for the problem.

Not shipping messy code makes sense. But, the debt metaphor is a useful tool to talk about existing “messy” code, compared to just calling it messy code. Looking at it as a debt lets you think about whether or not it’s worth paying off, and if so when, etc. The Technical Debt Quadrant (explained below) further classified this debt into 4 classes, which makes it even more useful to identify bad code as debt.

Technical Debt Quadrant

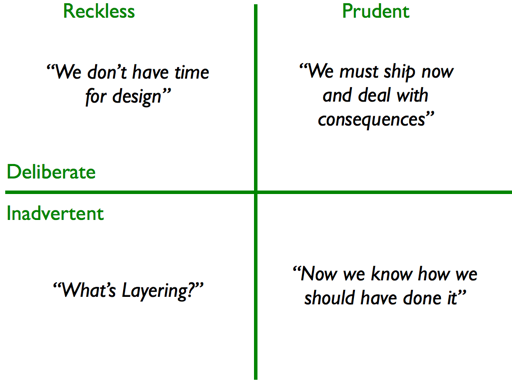

Martin Fowler came up with a Technical Debt Quadrant which incorporates other kinds of debt, along with the one Ward Cunningham originally defined.

Fowler comes up with two kinds of divisions of debt — Reckless vs Prudent and Inadvertent vs Deliberate.

When Ward says he’s against writing bad code, I think he means he’s never for taking on reckless debt. Uncle Bob’s mess is also what Fowler would call Reckless debt.

Reckless-Deliberate debt is code written out of not caring enough about the code, or not stopping to think about everything that’s going on with the code, or just being mentally lazy. Code-reviews seem like one good way to avoid this kind of debt.

Reckless-Inadvertent debt is something that’s hard to prevent. It sounds like unknown-unknowns territory to me. The developers or the team would probably benefit from improving their general design skills and/or getting some external help as consultants, etc.

Prudent-Deliberate debt is what Ward talks about, I think, in his video. You know your understanding is not good enough, but you aren’t yet sure what’s the right design is. You may gather more knowledge about the problem while the software is out there in the wild and being used.

Ward talks about better understanding. But, you may not always realize that your understanding is incomplete, when you are shipping the code. This I think would put it in the 4th quadrant - Prudent-Inadvertent debt.

Is everything tech debt?

The Tech Debt quadrant seems to make a lot of things seem to fit into the debt metaphor, but there are some things that I’m not sure about.

For example, it can be a significant time investment to update dependencies. Often, teams don’t update dependencies until it becomes absolutely essential — “don’t fix what ain’t broken”. This strategy of postponing of updates, to use the time for other things, seems like taking on a debt. But, I’m not sure which quadrant to put it into.

Why should I care?

Just calling code messy isn’t really qualifying the mess, and helping us talk about how to tackle it. Thinking about debt while taking decisions seems helpful, especially with further classification of debt into the 4 quadrants.

It helps think about whether we’d like to pay off debts we have taken, and to communicate with non-technical people the kind of “maintenance” or refactoring work we plan to take up, and why it is important to do so. The deliberate debt concept can be used to think and communicate about things we aren’t dealing with, right now, in the interest of shipping software quicker.

Keeping track and repaying debt

If a debt is something we can take on deliberately, and we can take on multiple such debts, what would be a good way to keep track of these debts?

Keeping a list of these debts that we periodically review, seems like a good idea. We check if our understanding has improved from the time we took on a debt, and take out time to incorporate it back into the code.

This list could just be a bunch of FIXMEs in the code with some detailed explanation of the debt, and why it was required, or just a list of issues in the issue tracker with a special tag to make it easy to find them.

Thanks to Shantanu Choudhary and Vivek Krishnaswamy for reading drafts of this post and giving helpful suggestions.